Week 6 Questions

5 Simulation Games

- Workplace Bias Simulator

Players take on the role of a hiring manager reviewing resumes. Subtle differences (names, schools, gaps in employment) influence candidate perception.

Goal: Reveal unconscious bias and show how structural inequality affects hiring decisions.

- Living Paycheck to Paycheck

A month-long budgeting simulation where players manage rent, food, transportation, medical bills, and surprise emergencies.

Goal: Show how poverty isn’t about “bad choices” but limited options and systemic barriers.

- Social Media & Identity Simulation

Players create a profile and make posts while managing peer approval, family expectations, and professional consequences.

Goal: Explore speech communities, identity performance, and social pressure (ties nicely to your sociology themes).

- Immigration Journey Experience

Players navigate paperwork, language barriers, job searching, and cultural adaptation in a new country.

Goal: Build empathy for immigrants and demonstrate structural challenges beyond individual effort.

- Campus Power & Privilege Game

Players experience college life from different perspectives (first-gen student, wealthy legacy student, working parent, etc.). Access to internships, networking, and free time varies.

Goal: Show how opportunity is shaped by social capital, not just motivation.

Game Response Week 6

Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes

- What made the experience fun or not? Virtual environments are fun cause we don’t get to play with them very often – I like the collaboration aspect of having to both describe two different things which don’t match but work together to solve a problem

- What is the motivating factor to get or keep players playing? To figure out how to not die and blow up – seeing if you can work together well

- Is the game persuasive, and what is it trying to get you to do outside of the game? I wouldn’t really call it persuasive per say, but it makes you realize how difficult it can be to successfully work together on things

- What is the game’s metaphor and which of the game’s mechanics standout? the metaphor is diffusing a bomb and working together, the mechanic of both players seeing two different things to accomplish the same goal is intriguing and makes it difficult yet fun

- How does the gameplay make you feel? Who does the game make you feel empathy for? It made me feel a little stressed and panicked, but mostly exhilarated to try and be a successful bomb diffuser, it makes me feel empathy for real bomb diffusers

- Is the game an activist game? If so what does the game play advocate for? It is not an outright activist game in my opinion, but if it was it advocates for clearer communication and thinking quickly in necessary tense situations

- Describe the game in 3 sentences or in the form of a haiku.

Confusing manual

A box with mini puzzles

Communicate or die

Also started my podcast game Children of the Sky – I haven’t played it enough to get a feel for it but it’s supposed to be an environmental impact activist game about spreading light and hope to darkness and we will see how that works – it does make me feel nice though

Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes: Game Reflection

- What made the experience fun or not?

The game is fun because it is very intense and chaotic in a good way. Everyone has to talk fast, listen carefully, and stay calm while the timer counts down. It can also be frustrating when people panic or misunderstand each other, but that stress is part of what makes the game exciting and memorable.

- What is the motivating factor to get or keep players playing?

The main motivation is teamwork and pressure. Players want to improve their communication.

- Is the game persuasive, and what is it trying to get you to do outside of the game?

Yes, the game is persuasive because it shows how important clear communication and trust are. Outside of the game, it encourages players to listen better, explain things clearly, and stay calm under pressure.

- What is the game’s metaphor and which of the game’s mechanics stand out?

The bomb is a metaphor for high-stress situations where mistakes have serious consequences. The standout mechanic is that only one player can see the bomb while the others can only see the manual.

- How does the gameplay make you feel? Who does the game make you feel empathy for?

The gameplay makes you feel anxious, rushed, and sometimes overwhelmed. The game makes you feel empathy for the bomb defuser because they are under constant pressure and depend entirely on others for help.

- Is the game an activist game? If so, what does the game play advocate for?

The game is not an activist game in a political sense, but it does advocate for cooperation and communication. It promotes teamwork, patience, and shared responsibility. It shows that success comes from collaboration rather than individual control.

- Describe the game in a haiku

Wires, beeps, ticking clock

Voices overlap in panic

Trust defuses fear

Spoon Buffet

Players: 2–5

Time: 15–20 minutes

Goal: Manage your daily energy (“spoons”) wisely and finish the game with the most spoons preserved, without burning out.

Theme: What Are “Spoons”?

Spoons represent mental, emotional, and physical energy.

You start each day with a limited number. Some things cost spoons, others restore them—and ignoring your limits has consequences.

Card Types

- Task Cards

Work, School, Chores

→ Cost spoons to complete - Self-Care Cards

Sleep, Exercise, Mindfulness

→ Restore spoons - Support Cards

Friends, Therapy, Family

→ Protect spoons or help counter Stress - Stress Cards

Anxiety, Overcommitment, Unexpected Events

→ Drain spoons unless managed

Setup

- Shuffle the full deck.

- Each player starts with:

- 10 spoons (use tokens, paper, or a tracker).

- Deal:

- 2–3 players: 7 cards each

- 4–5 players: 8 cards each

- Keep spoons visible to everyone.

Gameplay (Drafting Rounds)

Each round represents one day.

- Choose One Card

- Look at your hand.

- Secretly choose one card to play face-down.

- Reveal & Resolve

- All players reveal cards simultaneously.

- Apply effects immediately:

- Pay spoon costs

- Gain spoons

- Trigger stress effects

- Pass the Hand

- Pass remaining cards:

- Left on odd-numbered rounds

- Right on even-numbered rounds

- Pass remaining cards:

- Repeat until all cards in hand are played.

Card Effects

Task Cards

- Cost 1–3 spoons

- Worth points only if you can afford them

- If you cannot pay → take Spoon Debt (see below)

Self-Care Cards

- Restore 1–3 spoons

- Cannot raise you above your starting max (10 spoons)

- Multiple self-care cards stack

Support Cards

- Protect against Stress cards

- May:

- Reduce spoon loss

- Cancel a Stress card

- Be shared with another player (card text specifies)

Stress Cards

- Force spoon loss unless countered

- Some require another player’s involvement:

- Example: Overcommitment → another player must give you a Support card or you lose extra spoons

- If no help is given, consequences increase

Spoon Debt (Burnout Mechanic)

If you ever drop below 0 spoons:

- Take 1 Spoon Debt token

- Immediately reset to 0 spoons

- Each Spoon Debt = –2 points at the end of the game

Message: You can push through… but it costs you later.

End of Game & Scoring

When all drafting rounds are complete:

- +1 point for each spoon you have left

- –2 points for each Spoon Debt token

- Bonus points (optional):

- +2 points for balanced play (at least one Task, Self-Care, and Support card played)

Highest score wins.

Week 6 Mason Tosadori

- What made the experience fun or not? KEEP TALKING AND NO ONE EXPLODES

The experience was fun whenever you actually completed a part of the puzzle, but other than that it can be a little frustrating. Since I was the one in the goggles and not giving the instructions, I felt annoyed by waiting to be told what to do, and especcially annoyed when the information they give me is wrong. It seems really simple to me cause I just listen to the instructions, I don’t have to think.

- What is the motivating factor to get or keep players playing?

The motivating factor is to try and succeed to defuse the bomb within the time limit. The players want to keep trying after failing. The instructions become more clear with the more practice you get with the game, which makes you feel like your getting closer to winning with every attempt.

- Is the game persuasive, and what is it trying to get you to do outside of the game?

I don’t think the game is trying to be persuasive, it seems more like a rage game or party game where its supposed to induce chaos and frustration. Maybe it’s trying to get people better at listening as well as better at giving instructions.

- What is the game’s metaphor and which of the game’s mechanics standout?

The games metaphor has to do with working with a partner. Maybe it means that working with others can be difficult, but sometimes its needed. The mechanic that standsout is the fact that you need to have someone else to play. The game is multiplayer but not in the typical sense where you share a screen and play together, this game has someone playing the game, and someone reading the book.

- How does the gameplay make you feel? Who does the game make you feel empathy for?

The gameplay can make everyone feel frustarated. The player gets upset because they arent getting the right directions, and the book reader gets upset because they have a book with difficult instructions that are hard to understand, especially since you can’t see the bomb. The game makes empathy for people who work understress and people who have issues with communication.

- Is the game an activist game? If so what does the game play advocate for?

I don’t think it is. If anything maybe its for having people understand the stress that bomb squads go through, but I think that’s a stretch.

- Describe the game in 3 sentences or in the form of a haiku

you have 5 minutes, work with your teammate or else, you will blow up too

5 simulation idea

- A game where you take a test in class but you have to cheat to try and pass

- A game where you are an emergency responder and have to dispatch help

- A farming simulator where you have to go around and feed livestock and take care of plants

- an inventory managment game where you have to look at patterns and keep your store stocked, (supply and demand)

- A firewatch game where you sit in a tower and have to make radio calls and prevent fires/put them out

Game Design 2 Simulation ideas

Pet Adoption Simulation

You volunteer at an overcrowded animal shelter.

VR Mechanics:

- Feed, groom, and medically assess animals

- Learn each pet’s personality traits

- Match them with adopters based on compatibility

- Physically kneel to comfort scared animals

- Hand-feed or gently brush fur using motion controls

- Heartbeat audio when animals feel safe

Horror Vr Game Abandon Hospital

VR Mechanics:

- You explore a condemned hospital overnight.

- Ghosts are tied to unresolved stories.

- You piece together what happened through environmental clues.

- Instead of fighting ghosts, you calm them by uncovering truth.

Coral Reef Simulation

VR Mechanics:

You’re restoring a dying reef ecosystem.

- Plant coral fragments

- Remove invasive species

- Monitor water temperature & pollution

- Protect reef from storms

Space simulation vr game

VR Mechanics:

- Exit the airlock

- You’re a space station repair technician orbiting Earth.

- Tether yourself

- Repair satellites and station panels

- Monitor oxygen and suit integrity

- Full 360° zero-gravity movement

- you push off surfaces to move.

Collaborative Baking Game

VR Mechanics:

- Ingredients float away if not secured

- One player stabilizes gravity controls

- One mixes

- One bakes

- Timed customer orders

- Flour clouds float everywhere. Someone always drops the cake.

Game Design 2 Week 6 Simulation

Aleah Dudek

Keep Talking No one explodes

- What made the experience fun or not? The game is fun because it forces intense communication under pressure. It can become frustrating if communication breaks down or if players don’t listen carefully.

- What is the motivating factor to get or keep players playing? The challenge of increasingly complex bomb modules. The communication can become very difficult if the other player isn’t good at directions.

- Is the game persuasive, and what is it trying to get you to do outside of the game? Yes, it persuades players to value clear communication, patience, and collaboration. In the real world it can help players inhabit listening skills, strategy, and staying calm under stress.

- What is the game’s metaphor and which of the game’s mechanics standout? High stakes problem solving depends on communication, not individual intelligence. Bouncing back and fourth between the players and how easily one explains what they see and how well the other follows direction.

- How does the gameplay make you feel? Who does the game make you feel empathy for? It makes me stressed , but also watching other people play is kind of humorous as you sort of watch them struggle in the game. It makes you feel empathy for the one trying to describe the situation since they can’t directly see what’s going on.

- Is the game an activist game? If so what does the game play advocate for? I don’t think its necessarily and activist game, but I think it can sort of advocate foe collaboration under stress, and how to learn ti work in those situations.

- Describe the game in 3 sentences or in the form of a haiku. Ticking wires and fear

Voices clash, pages turning ,

Trust defuses time.

Game Maker’s Play Test Notes: Bad Advice

- What questions did your players have?

The players had questions regarding how to determine the winner. - How quickly did they learn to play?

I would say it took the players about 10 minutes to learn, even though the directions were quite confusing. - What kinds of interactions did the players have?

The players interacted with the judge each round when deciding who had the best advice card and reality check card. - What confused players?

The confusion stemmed from the game’s objective, as the notes indicate the need to “Fix the rules” and clarify that the objective is to be the best therapist to gain points, while “winning bad therapist is losing points.” - What made players excited?

What made players most excited was getting to sift through each different type of prompt that they could choose from. - What did your players enjoy doing?

The players enjoyed selecting funny advice cards. - Did any aspect of the game frustrate players?

The biggest frustrating aspect was understanding the rules, which I was working on defining. The point of confusion about the rules and winning conditions. - What did your players learn /take away from your game? Was that what you intended?

Players learned good coping skills and elements to make it through life. - What is your plan to address player questions, confusion, and frustration?

The plan includes to “Fix the rules,” clarify the objective as being the best therapist to gain points, and to clarify that winning “bad therapist” is losing points. The game will be structured to have one round of bad advice and one round of good advice, using sets of good and bad advice cards. Mechanical changes include having players “play two cards every turn,” setting the “hand limit go down to three cards,” and possibly replenishing cards when a player is down to one. The round itself will change to first picking the best advice and then redoing the round with a “reality check” card to leave room for open discussion. - If your players didn’t get your intended message, what will you change?

The change plan involves new scoring and mechanical considerations: the objective is to be the best therapist to gain points, with the advice card winning three points, the reality check card winning five points, and all points being added up at the end of the game to see who wins. Other changes include keeping the “prompt card” if a player wins the reality check round, and keeping the “bad advice card in a separate pile to keep track of.” For inspiration, the designer plans to look at the game Gloom and look up the game Wavelength.

Game Reflections

Merideth’s Game:

- What made the experience fun or not?

- The experience was made fun by being in last place.

- What is the motivating factor to get or keep players playing?

- The motivating factor to get or keep players playing is the ability to destroy planets.

- Is the game persuasive, and what is it trying to get you to do outside of the game?

- Yes, the game is persuasive because it is trying to get you to take a look at the way we treat our earth outside of the game.

- What is the game’s metaphor and which of the game’s mechanics standout?

- The game’s metaphor is to treat our environment with respect, and specifically to preserve the planet.

- The standout mechanic is the idea of being able to destroy planets.

- How does the gameplay make you feel? Who does the game make you feel empathy for?

- The gameplay makes the player feel excited to jump into the game, and it makes the player feel empathy for our planet.

- Is the game an activist game? If so , what does the game play advocate for?

- Yes, the game is an activist game, and the gameplay advocates for reflection.

- Describe the game in 3 words.

- The game is described as “Creative black holes.”

Cards and meaples were confusing. I like the mechanics. The planet cards were interesting to use in order to gain things in elements. Black holes were nice to touch to create an incentive to destroy planets to gain resources.

Andrews Game:

- What was the most frustrating moment or aspect of what you just played?

- The most frustrating moment was when the player was trying to move forward but could only move back, which required them to move back off the board or else they could not move anymore.

- Was there anything you wanted to do that you couldn’t?

- The player wanted to be able to move forward more.

- If you had a magic wand to wave and you could change, add, or remove anything from the experience, what would it be, what should improve the next version?

- The player would add another die to see if there was anything more they could do with the turn to keep the game moving, but noted that you have to land on white.

- The player also had a question about what happens when you go too far left and whether their perspective or direction would change.

- What was the game’s narrative/themes/message?

- To be honest, the player did not really gather a theme or a message at all.

- How did the game make you feel?

- The game honestly made the player feel bored and dragged on.

- Describe the game in three words.

- The game is described in three words as “potential to grow.”

Games Feedback – Extra Steps, Modified Jenga, Battle of The Suits, ONE: Evil Uno

– It was frustrating how many cards I had to pick up.

– My favorite moment was winning and the counting aspect of the game.

– There wasn’t anything I wanted to do that I couldn’t.

– If I could change anything, I would add counting backwards.

– I think the game’s narrative and theme was counting.

– I would describe it as unreasonable, interesting, and fun.

– A question I had: Do we have to start with 1? or a card from the pile?

– The reason I said unreasonable for describing it is because we just picked up cards until we got a higher number, which was a lot. Maybe if it was just picking up one card and moving on would be better.

MODIFIED JENGA

– The most frustrating moment was the blocks falling really fast, obviously lol. Maybe more blocks would be better, or playing around with the form of the tower?

– My favorite thing about this is that it’s really interesting and the tasks were pretty funny.

– If I were to add anything, I would probably add more cards/tasks/possibilities.

– I think it would also be better to clarify in the rules that there are notes on the blocks themselves that align with the cards. It was confusing at first.

– The games narrative/theme was to pick the blocks up and don’t make the tower fall.

– I would describe the game as interesting, fun, and creative.

– It’s a really engaging and interesting game, again, just more tasks/rules I think would keep it engaging for a longer time.

BATTLE OF THE SUITS

– For this game, Professor Ames told us to play it in a group of 5 instead of 1v1 how it was intended. From this, we tackled how to go about that.

– It was frustrating not knowing who to attack and not attacking the person who is attacking you.

– I really liked the clear cards and the hp aspect. The attacking was really fun as well.

– If it were to expand to a 5 player game, I would add the ability to choose who you attack.

– Even for 1v1, I think it would be good to add something that tracks the hp as the game goes on.

– The game’s theme was to basically stay alive and keep your hp.

– I would describe the game as interesting, entertaining, and competitive.

– A question I had: Do we pick up a card after each turn? Should we have 5 cards the whole game?

– I would make more clear rules on who to target, attack, and shields.

– I would also add more cards.

ONE: EVIL UNO

– It was frustrating not knowing what each card means. You would have to play it a lot to get more familiar with each card; a lot of card varieties.

– I loved how funny and different it was. It wasn’t just an uno knockoff.

– I would change the F-U card and make it into something that you can use against others.

– I would also make fewer +4 or +something cards. Players ended up gaining way too many cards, up to half the stack which gets annoying because it never ends.

– Maybe a way to get back in the game would be interesting?

– I would describe the game as different, evil and funny.

– Definintely fits evil uno!!

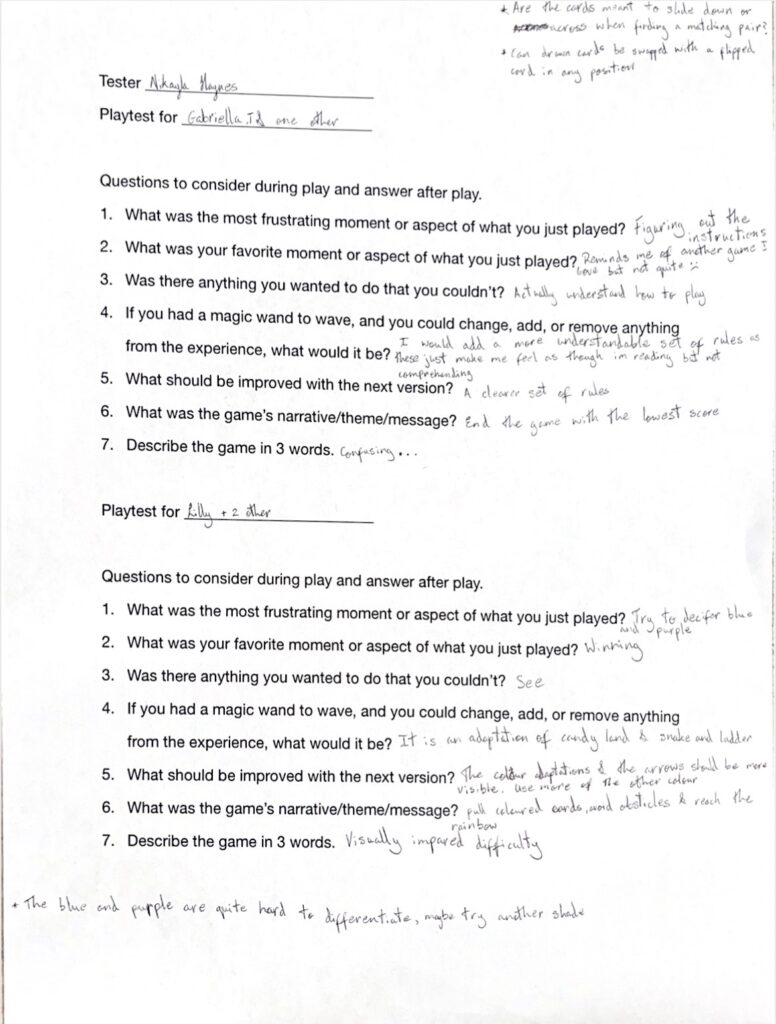

Rainbow Dash & Gabriella’s game (not sure of the name)

Cat rush (overall notes)

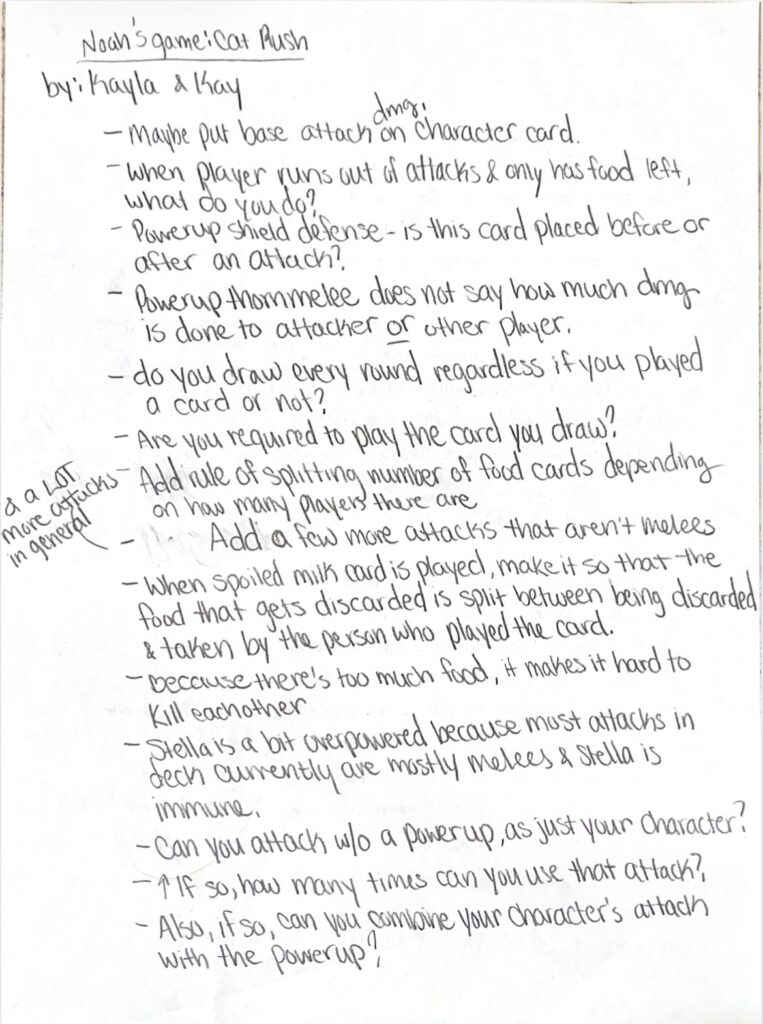

Noah’s Game: Cat Rush

By Kayla & Kay:

- maybe put base attack dmg on the character card itself

- When a player runs out of attacks & only has food left, what do you do?

- Powerup shield defense- is this card placed before or after an attack?

- Powerup thorn melee does not say how much damage is done to attacker or other player since it hits both

- Do you draw a card every round regardless if you played a card or not?

- Are you required to play the card that you draw?

- Add rule of splitting number of food cards depending on how many players there are

- Add a few more attacks that are not melees

- Add a lot more general attacks since there is more food than attacks

- When spoiled milk card is played, make it so that the food that gets discarded is split between being discarded & taken by the person who played the card

- Because there’s too much food, it makes it hard to win and kill each other

- Stella is a bit overpowered because most attacks in deck currently are mostly melees & stella is immune

- Can you attack w/o a powerup as just your character?

- If so, how many times can you use it?

- Also, if so, can you combine your character’s attack with the powerup?

Battle of The Suits and Pirates Playtest Feedback

Battle of the Suits

– The most frustrating moment was that it did not end. I feel like this is supposed to be a fast-paced game.

– My favorite aspect was using the Ace as a high point card. However the instructions did not specify if Ace was played as 1 or 13.

-I would adda a way to track HP and shield points.

– The clarity/wording of the rules could be improved.

– In 3 words: more complex war

Pirates

– Takes a while to learn, which is frustrating, but it gets easier after that.

– My favorite aspect is the roleplay/imaginative part. Overall, great immersiveness.

– I would change the character sheets so that the information is easier to absorb; the multiple pages felt overwhelming.

– Moves/actions could be explained better.

– I loved the pirate adventure narrative.

– In 3 words: D&D Pirate Parody