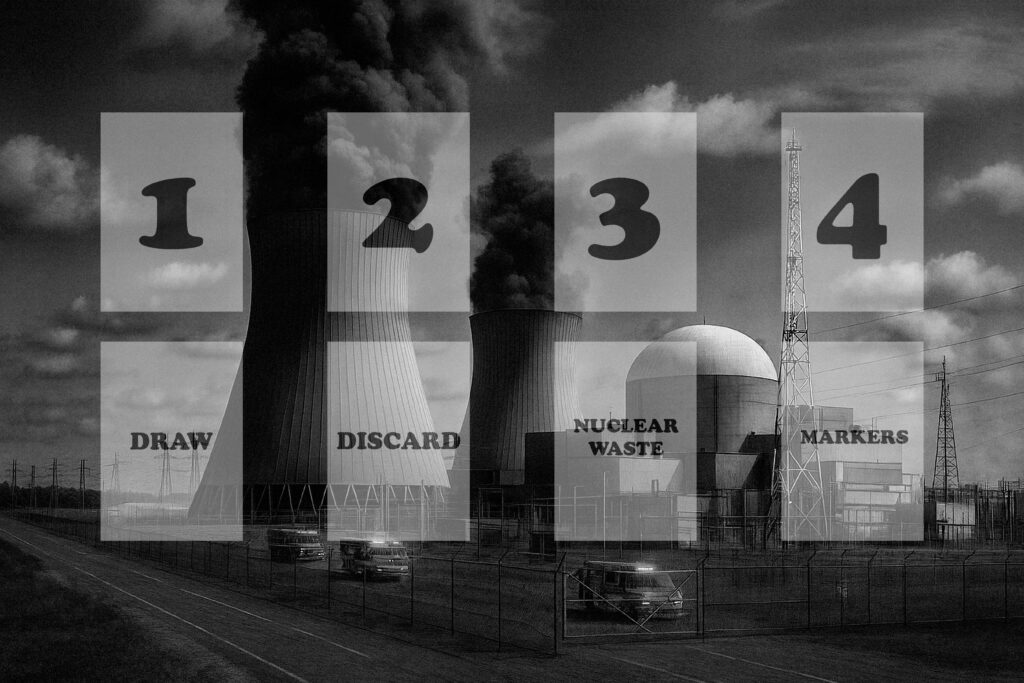

This is the game mat design I chose for Reactor 21. The mat was created with the AI generated image as the backdrop, and the grid/text/mat sections were set up by me in Photoshop CC.

design courses, syllabi, schedules, resources and policies

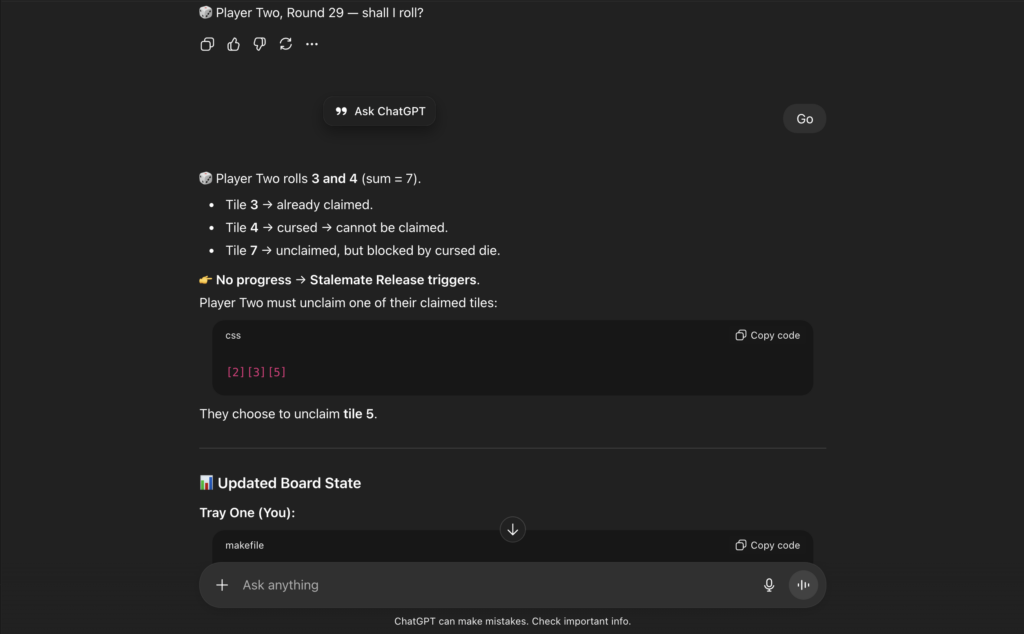

Boxed In came from wondering what a competitive version of Shut the Box might look like. Giving each player their own tray made the game immediately more interesting, and most of the development came from quick playtests with ChatGPT—mainly experimenting with doubles penalties, pacing issues, and ways to keep the game from stalling out.

We found a few solid ideas, like the Stalemate Release rule, but I never quite reached a final version that felt fully balanced. Still, the process paid off. A lot of what we learned while testing Boxed In directly shaped the design of Reactor 21, which grew out of the same experiments but landed in a much stronger place.

In the beginning, both players are just getting their boards started. You roll, claim a few easy tiles, and see what kind of shape your board is taking. It’s mostly about opening things up and seeing where the numbers fall.

As the game settles in, you’re making small adjustments based on what the dice give you. The doubles effects add a little movement, but most of the time you’re just trying to keep your board flexible and avoid boxing yourself into a corner.

Toward the end, there are fewer open spots and each roll gives you a couple of decisions to think through. The Stalemate Release rule helps keep things moving, and you’re mostly trying to keep the board workable long enough to reach your goal.

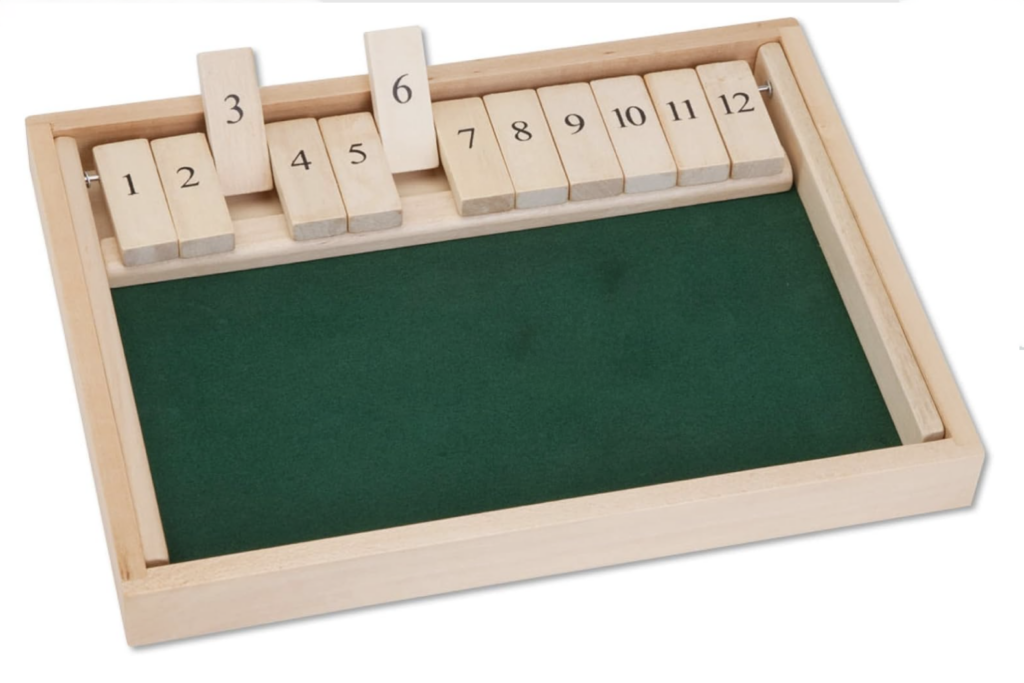

The boards were purchased directly from Amazon. I’ve attached a screenshot of the product photo from the website.

And this is a screenshot of how my playtest with ChatGPT looked on my screen…

There was a game that I was attempting to develop at the same time I was starting out with A Game About Colors… This other game was called Boxed In.

Boxed In came from wondering what a competitive version of Shut the Box (the classic pub game) might look like. Giving each player their own tray made the game immediately more interesting, and most of the development came from ongoing playtests with ChatGPT—mainly experimenting with doubles penalties, pacing issues, and ways to keep the game from stalling out.

We found a few solid ideas, like the Stalemate Release rule, but I never quite reached a final version that felt fully balanced. Still, the process paid off. A lot of what we learned while testing Boxed In directly shaped the design of Race to 65, which grew out of the same experiments but landed in a much stronger place.

In the beginning, both players are just getting their boards started. You roll, claim a few easy tiles, and see what kind of shape your board is taking. It’s mostly about opening things up and seeing where the numbers fall.

As the game settles in, you’re making small adjustments based on what the dice give you. The doubles effects add a little movement, but most of the time you’re just trying to keep your board flexible and avoid boxing yourself into a corner.

Toward the end, there are fewer open spots and each roll gives you a couple of decisions to think through. The Stalemate Release rule helps keep things moving, and you’re mostly trying to keep the board workable long enough to reach your goal.

Top two ideas, each in only one sentence

A Game About Colors, More or Less is a deduction game where players compare subtle color differences and guess which card shows more or less of a chosen color.

Reactor 21 is a cooperative game where two players work together to stabilize unstable reactors by managing cards, preventing meltdowns, and keeping the system balanced.

Here are my five game ideas that revolve around the idea of collecting:

Red Flag Rally is a team party game where players collect “red flag” personality traits from fictional characters and work together to decide whose imaginary date is the least disastrous.

After Hours Heist is a collaborative strategy game where players collect tools and inside intel to pull off a late-night break-in, making risky choices that raise tension but require the whole group to commit.

Secret Signals is a social deduction game where players collect coded clue cards and have to share information in subtle, slightly flirty ways to reveal who in the group is actually on their team.

Flirt & Fumble is a cooperative chaos game where players collect “effort points” by attempting mildly awkward or bold social challenges written on cards the group draws together.

Moonlit Market is a mysterious team game where players collect forbidden items from a nighttime bazaar and must negotiate with strange NPCs and each other while keeping certain temptations in check.

5 game ideas that revolve around a single theme of of your choice. if your theme is time traveling ducks, then all five ideas need to be different games that utilize the same time traveling ducks theme any idea off theme will not earn a point. continue to follow the idea formatting rule:

I accidentally already covered this topic in week 3, regarding games revolving around color. One of the ideas morphed into the original concept for A Game About Color, More Or Less. The original rules of that game were as follows:

A Game About Colors, More or Less… — Version 1 Rules

SETUP

GAMEPLAY

Player Turn Sequence:

a. Move the top two cards from Pile A: one to B, one to C, both color side up.

b. Roll the six-sided die to determine the active color using the board’s key.

c. Compare the two revealed color sides on B and C, declaring which is more/less of the rolled color.

d. Flip both cards to reveal numeric values for C, M, Y, R, G, and B.

Higher number = more. Lower number = less. Matching values = Good Luck (automatic win).

e. Correct or Good Luck → player keeps both cards. Incorrect → both to discard pile D.

f. Turn ends; next player draws new cards to B and C and repeats.

END OF ROUND AND WINNING

Example of Gameplay

It’s Maya’s turn, and she’s the active player.

She takes the top two cards from Pile A and places one on B and one on C, both color side up.

She rolls the die and gets a 2.

According to the color key, a 2 means she has to compare the cards for magenta.

Maya looks at the two color swatches on B and C. After studying them, she decides that the card on B looks like it has more magenta than the card on C. She says, “B has more magenta.”

Now she flips both cards over to check their values.

Card B shows a magenta value of 58.

Card C shows a magenta value of 42.

Her guess was correct, so she takes both cards and adds them to her personal pile.

Her turn is over, and the next player repeats the same steps with two new cards.

5 game ideas that involve collaboration use the following formate : [Game name] is a [category of] game in which [the players or their avatars] [do or compete or collaborate for some goal] by [using tools the game provides them]

Prism Teamwork is a cooperative board game in which players work together to fix broken colors by using color tiles to match and complete patterns on the table.

Color Detectives is a team guessing game in which players try to figure out which color is missing or out of place by using clue cards and talking it out together.

Rainbow Builders is a collaborative building game in which players work as a team to create a big rainbow by placing colored blocks or cards in the right order.

Shade Garden is a shared strategy game in which players take care of a garden that changes colors and help each other mix the right shades using simple color-mixing cards.

Color Path Adventure is a cooperative path game in which players try to travel across a map by matching colors and using special color cards to help teammates move forward.

Was it fun? Absolutely, once we understood the rules.

What were the player interactions? The player interactions were timid at first, as we were figuring out rules and strategy. Once we all got a grip on what we were doing, we were all enthusiastic about starting over and going to war. That’s when the interactions became a lot more fun.

How long did it take to learn? The gameplay rules were very straightforward. The strategy took a bit longer to figure out… Perhaps 20 minutes…

What was the most frustrating moment or aspect of what you just played? No frustration at all.

What was your favorite moment or aspect of what you just played? Once we all figured out some strategy, it was time to go to war. That was fun.

Was there anything you wanted to do that you couldn’t? Nothing comes to mind. I feel like nothing was working. That feels perfect to me.

If you had a magic wand to wave, and you could change, add, or remove anything: I wouldn’t change a thing.

Is this a game you would play again? I purchased the game on my iphone immediately after class.

Analyze the game using the 3 act structure. The opening act would be the setting up the economy based on initial decision on allocation resourses. The second act involves the majority of the fun, where each player goes on a land grab with decisions on how to proceed against adversaries. The final act involves thinning out the weak based on who played their cards right, as the strongest race toward victory conditions.

What are the collaborative and or competitive aspects of the game? I found the entire game to be collaborative.

What is the game’s metaphor and which of the game’s mechanics standout? Catan is a strategic resource game where players grow their settlements by collecting, trading, and converting resources into roads, buildings, and points. The engine building mechanic of the game is what stood out to me.

The process of developing the graphics was AI guided, mostly because illustration is more of a weakness than a strength to me, and I couldn’t find a photo showing what I was looking for.

Unless stated otherwise, any AI image generation was done in ChatGPT.

I started by generating a reactor image that I could use as the base of the design, with both a normal and ‘post-apocalyptic’ vibe…

I decided to go with the post-apocalyptic vibe. This was the prompt that generated the image:

Prompt used:

A striking daytime photo captures a nuclear power plant beneath a brooding sky, with thick black smoke rising from two towering cooling structures. The scene is punctuated by a smooth-surfaced reactor building, a lattice communication tower, and flashing emergency vehicles, all framed by grim, muted grays and occasional vivid reds, enhancing the dramatic atmosphere of the image.

I knew I had to design red, yellow, and green markers for the gameplay, and I ended up with this AI graphic:

Prompt used:

Three small, glossy plastic game tokens arranged in a row on a dark matte background. Each token is embossed with a simple symbol: a red token with a nuclear hazard icon, a yellow token with an exclamation warning icon, and a green token with a leaf eco-symbol. Soft, even studio lighting, clean shadows, photorealistic texture, top-down view.

I decided that the box should look like the dark reactor photo wrapped around the box. I also included a deck of cards with the reactor wrapped around the box.

Prompt:

A realistic product-photography scene on a solid black background. A large rectangular board game box titled “REACTOR 21” lies flat on the table. The box uses a military stencil font for all text. The artwork on the box is a dark, dramatic image of a nuclear power plant with cooling towers emitting thick black smoke and emergency vehicles below. The box is 18 inches long and dominates the left side of the frame.

To the right of the box is a standard-sized Bicycle-style deck of playing cards, standing upright. The deck has the same nuclear-reactor artwork framed inside the classic Bicycle-style layout, but with the title “REACTOR 21” in a military stencil font instead of the Bicycle logo. White borders and the familiar tuck-box shape are clearly visible.

In front of the box are multiple small game tokens, each exactly 0.5 inches in diameter, arranged closely together: four red tokens embossed with a radiation symbol, six yellow tokens embossed with an exclamation point, and five green tokens embossed with a leaf symbol. The tokens are thick like premium bingo chips. All tokens are proportionally tiny compared to the 18-inch box. Lighting is soft, even, and neutral to ensure the red, yellow, and green tokens are equally visible without glare.

The overall image has a dramatic but clean studio aesthetic, with sharp details, accurate object proportions, and a cohesive, cinematic tone.

The actual game board was composed mostly in Photoshop, and it will get a separate post as it was a completely different process.

Reactor 21 changed quite a bit as I tested different versions of it. The basic idea was always there—two players trying to keep a failing reactor stable—but it took some back-and-forth to figure out what actually made the game interesting. Early versions had the right intention, but some of the mechanics didn’t create the amount of teamwork or pressure I wanted. The game felt like it needed a bit more structure around how instability spreads, what happens during a meltdown, and how the players recover from setbacks.

Most of the improvements came from simply seeing how people reacted to certain moments in the game. Some rules felt too loose, and others were a little unclear in how they resolved. Adding the Nuclear Waste pile, tightening the meltdown rules, and clarifying how cards move between piles helped everything feel more intentional. The goal was always to keep the experience focused on communication and shared decision-making, and those adjustments moved the game in that direction.

During all of this, ChatGPT was helpful for keeping things organized. Any time I adjusted a rule or tried a different way of handling a reactor event, I used ChatGPT to help rewrite the sections cleanly, make sure the terminology stayed consistent, and compare versions so nothing got lost. It also made it easier to step back and look at each revision as a whole instead of just patching small pieces. The mechanics themselves still came from testing and intuition, but having a tool to structure everything made the development process a lot smoother.

Reactor 21 ended up feeling more balanced and readable because of that steady cycle of testing, revising, and tightening the language around the rules.

The three acts of the game are as follows:

Act 1 – Getting your footing

The game starts off pretty gentle. You’re drawing cards, placing them where they fit, and getting a feel for how the reactors behave. Most cards go somewhere without much trouble, and the token tracks are empty, so nothing feels dangerous yet. This is where you learn the rhythm: keep totals tight, stabilize when you can, don’t waste options.

Act II – Things start heating up

Now the reactors are filling up, and suddenly every card matters. A placement that was easy earlier now feels risky. You’re choosing between Instability and Meltdown more often, and both choices actually hurt. The Nuclear Waste Pile kicks in and you start to feel the deck thinning out. This is where the team talks things through, plans moves, and tries to stay one step ahead of the system.

Act III – Hold it all together

By the end, everything’s tense. One bad draw can end the whole run, and every card feels like it might be the last piece you need—or the thing that breaks the grid. You’re trying to lock down those last stabilizations before either track fills up. When the final reactor hits 21, it feels earned; if the system blows, it’s usually by a hair.

(Final thought created with the assistance of AI, using my input)

As I refined A Game About Colors, More or Less, the color system became one of the most important aspects of the design. Early versions relied on fully saturated colors, which made the comparisons visually clear and, in many cases, too easy. During testing, it became obvious that players could identify the stronger or weaker color channels with very little effort, which reduced the level of deduction the game was meant to encourage.

To address this, I shifted the palette to include added black (K) values between 30% and 70%. Lowering saturation created a more subtle, more challenging set of swatches. Colors that once felt predictable became more ambiguous, and players had to make more thoughtful evaluations based on small differences, rather than relying on obvious saturation cues. This adjustment aligned the visual experience more closely with the intentions of the mechanics.

Throughout the development process, ChatGPT was used as a collaborative tool to help build, refine, and organize the rule set. It played a role in structuring the language of the rules, maintaining consistency across versions, documenting changes, and evaluating how each update affected clarity and player experience. It was also useful for keeping a clean version history and ensuring that revisions—such as the shift to a reduced-saturation deck—were incorporated accurately and consistently. The core design decisions remained my own, but ChatGPT helped make the documentation process more efficient and reliable.

This combination of iterative testing and structured rule development resulted in a color system that better supports the game’s deductive, perception-based gameplay.

Act 1 – Getting a feel for the deck’s color language

Early on, players are mostly just getting acquainted with how the deck moves. They make a guess, flip the card, and start noticing which kinds of shifts catch their eye — a bump in brightness, a little pull toward red, or a change in saturation that didn’t seem obvious at first. It’s basically a warm-up for the eyes, where players start realizing that the game isn’t about naming colors; it’s about noticing how they behave.

Act 2 – Learning what actually matters in a swatch

Once everyone has a few cards in front of them, they naturally start leaning on simple bits of color theory — whether they mean to or not. Some players pay attention to value first, because brightness jumps out. Some start tracking saturation because muted colors hide shifts better. Others zero in on hue and notice how small moves between neighbors (like teal to blue-green) feel trickier than big jumps. This is where players start building their own internal system for judging the cards, one clue at a time.

Act III – Stay consistent with the system you’ve built

The game doesn’t suddenly get more intense toward the end — it just asks you to stick with whatever approach you’ve developed. By this point, players have their own way of reading the swatches, and the last part of the game is about trusting that instinct. Maybe you’re watching for low-saturation curveballs, or maybe you’re checking how the brightness sits against the last few cards you saw. It’s steady, calm decision-making — more about consistency than pressure — and the satisfaction comes from seeing how well your eye held up across the whole run.

Race to 65 didn’t change too dramatically as it developed. Most of the core structure was there from the beginning; the main work was just tightening the rules and making sure everything felt clear and consistent. A few of the early versions had small gaps or places where players weren’t totally sure how to handle certain situations, so the updates were mostly about smoothing out those rough edges.

The biggest adjustments were clarifying how tiles flip, how players advance toward the target number, and how the end-of-game callout works. These weren’t major changes, but they helped the game run more cleanly and made the turns feel more intentional without adding complexity.

ChatGPT was helpful mostly on the documentation side—rewriting sections for clarity, keeping the terminology consistent, and making sure each version lined up with the previous one. The game itself didn’t go through big mechanical shifts, but having support to organize the rules and clean up the language made the whole process easier.

The three acts of the game are:

Act I – Getting started

The game opens in a pretty relaxed way. Players start flipping tiles, getting a feel for their numbers, and easing into the rhythm. There’s no pressure yet—just settling in and seeing how the early moves shape things.

Act II – Building toward the goal

As the game moves along, players start paying closer attention to their totals and making more thoughtful choices. It’s still simple and approachable, but you do get that feeling of trying to outpace the hourglass a little. Small decisions start to matter, and players begin watching how close everyone is getting.

Act III – Making the final call

The endgame comes into focus once players approach the target number. At this point, the game turns into a light race against time and each other—just trying to hit the number cleanly without going over. It’s not intense or heavy; it’s more like that moment in a puzzle where you can feel you’re close, and you’re trying to line everything up just right before someone else finishes.