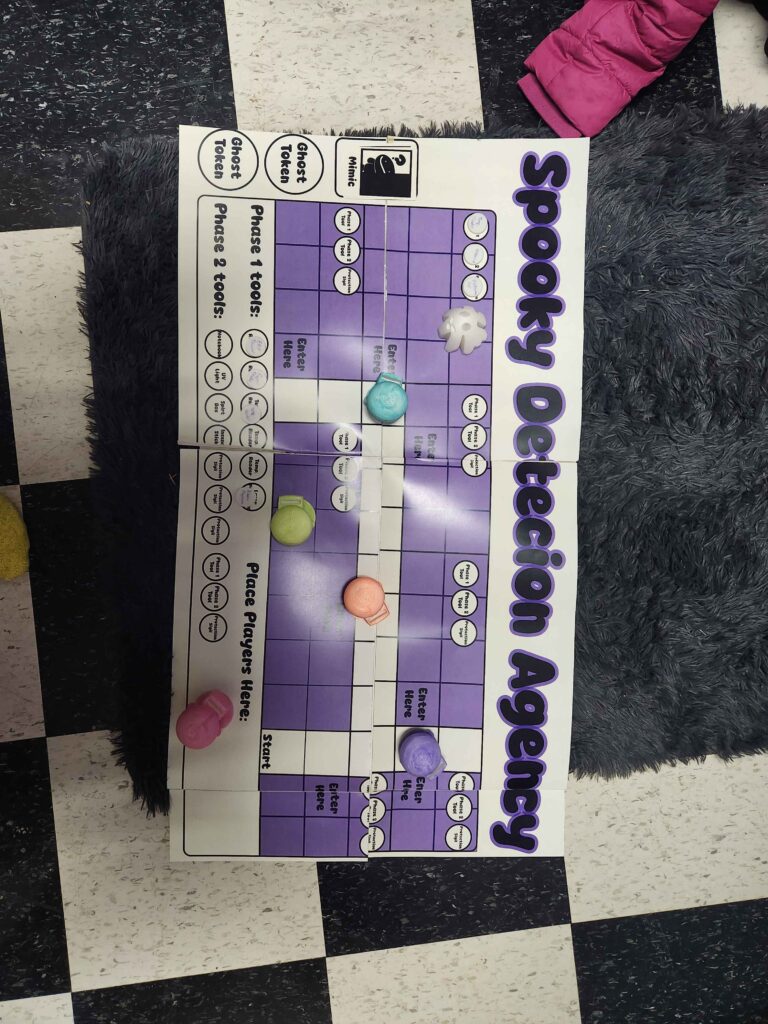

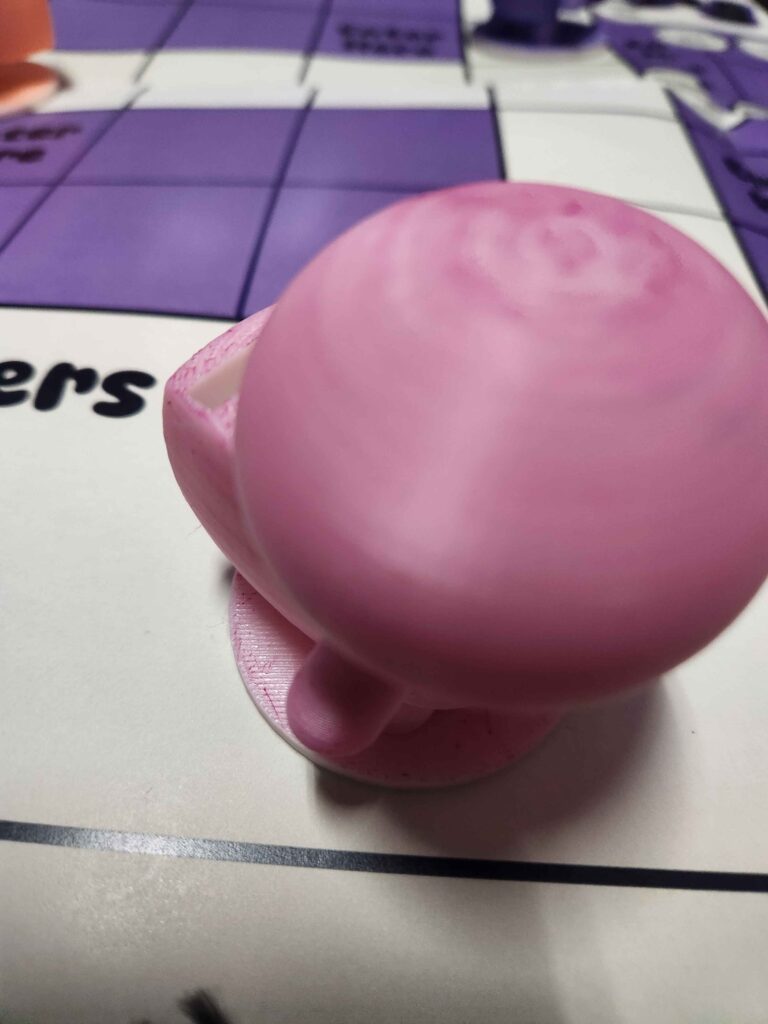

Final Project: Spooky Detection Agency

For my final project I deiced to make a board game based on ghost hunting. This was the 3rd attempt for a game like that’s, as previous iterations were tough for users to understand. This one has a better quaily board, colored chacarer tokens and updated rules. I wanted to dye the players, however rit dye was extreamly messy and didnt adhere well, so alcohol based markers were a subsitute, otherwise all pewioces are 3-D printed or cardstock.

Weeks 12-13 Question Sets

Question Set 1

- Working prototypes are intended for evaluation by playtesters and potential publishers, while display prototypes, with finished art and components, are intended for the eyes of distributors or chain buyers.

- Publishers want to see a clean, playable prototype. The game needs a clear set of rules so that playtesters can properly test the game. Without rules, the working prototype fails.

- According to Dale Yu, prototypes should look clean and well-made for a good first impression. Rules should be clear and correct, maybe even with diagrams and pictures to help first-time players understand how the game works. Components like cards, card sleeves, stickers, and paper are essential to make a clean game. Finally, he says if you want people to get excited about a game, send them home with a full, playable copy of it so they can play on their own time.

- Richard Levy’s first piece of advice is to be prepared. He also says to remember that information is power, meaning you should research the company you are publishing to and try and find other inventors to talk to about your game. He suggests selling yourself first and handling rejection well. Keeping your ego in control and having realistic expectations for a presentation. Finally, he suggests that inventors do multiple submissions of a game (revisions) and keep in mind how a trademark can impact their game being published.

- Pitching your game to small to mid-sized publishers in the hobby games industry is a suggested route to take.

- Publishers look for the fun factor, player interaction, immediacy of play, strategy, an interesting theme, an immersive experience, an interrelated theme, solid, innovative rules and mechanics, easily manufactured components, compatibility with other products, the correct target market, a good title, expansion potential, multi-language capability, easy demoing, and collectibility only if necessary.

- A good set of rules usually includes these subheaders: Overview, Components, Setup, Gameplay, Card types, Endgame and winning, Example of play/strategy hints/optional rules/game variants/glossary, and Credits.

Question Set 2

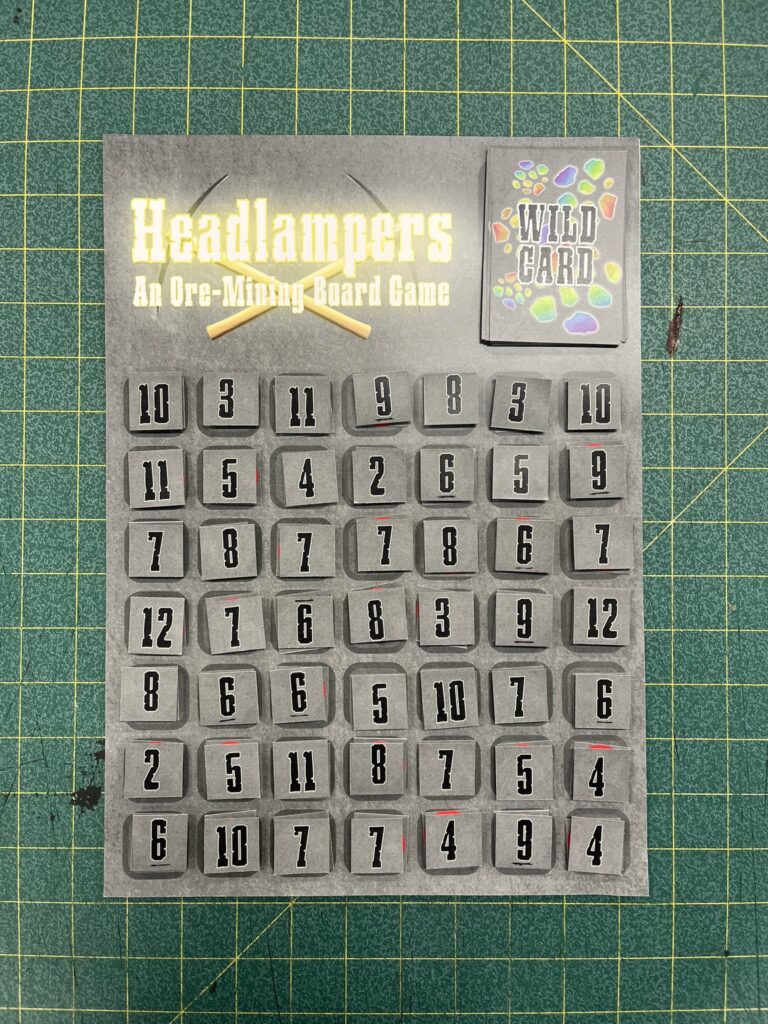

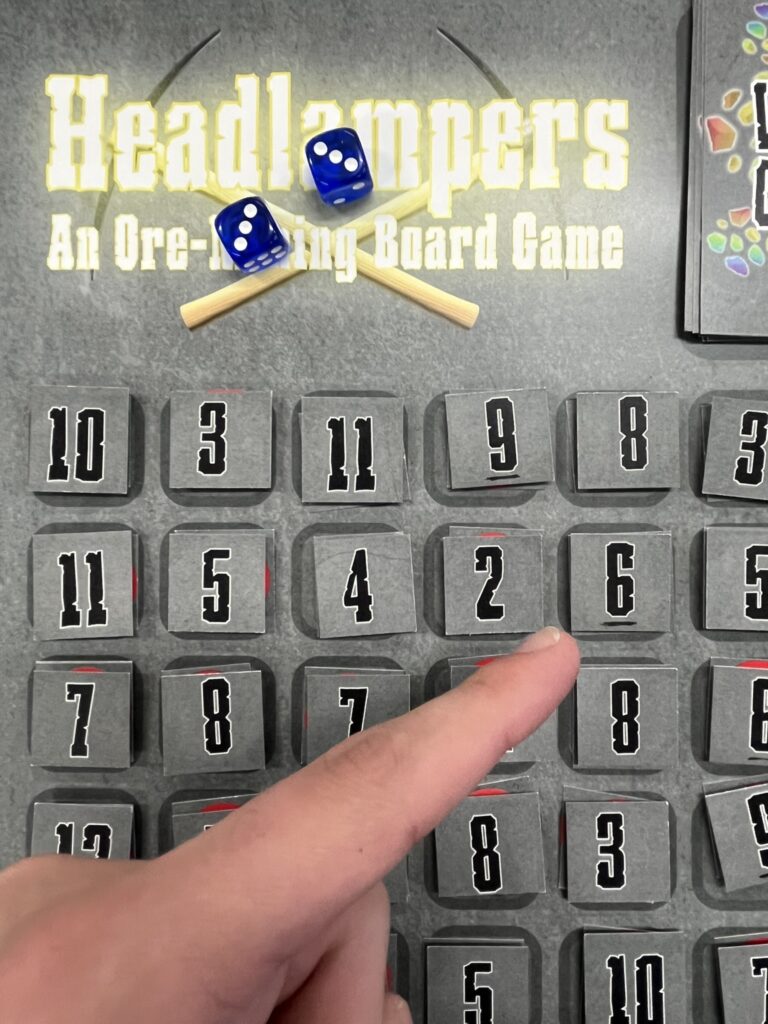

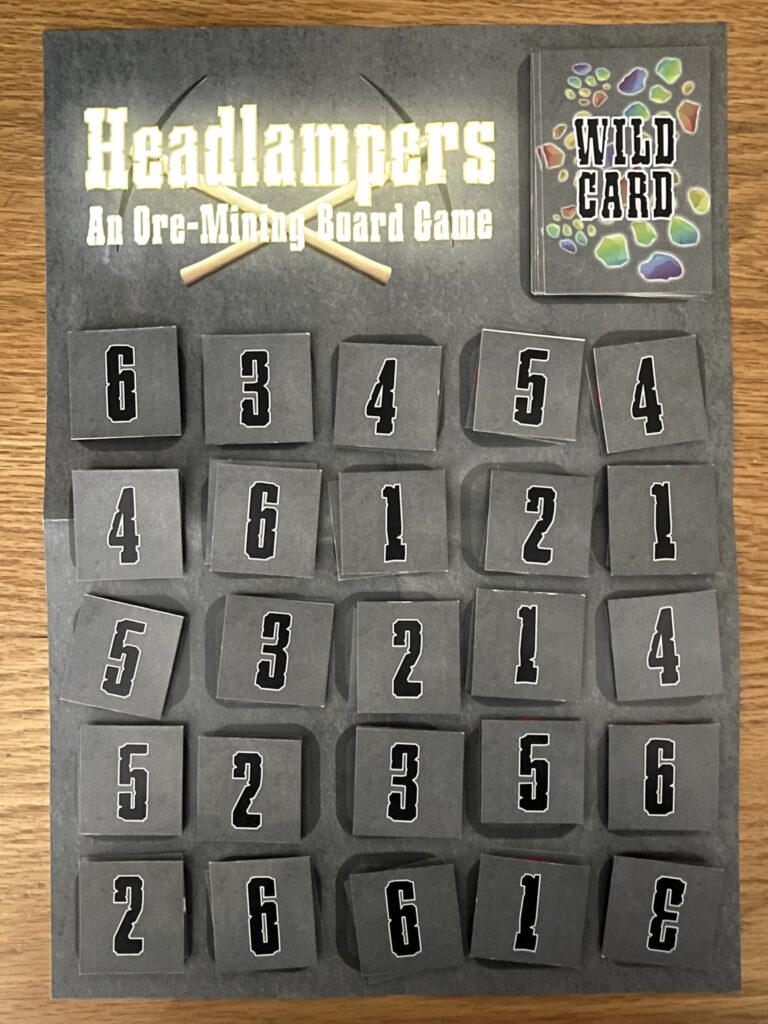

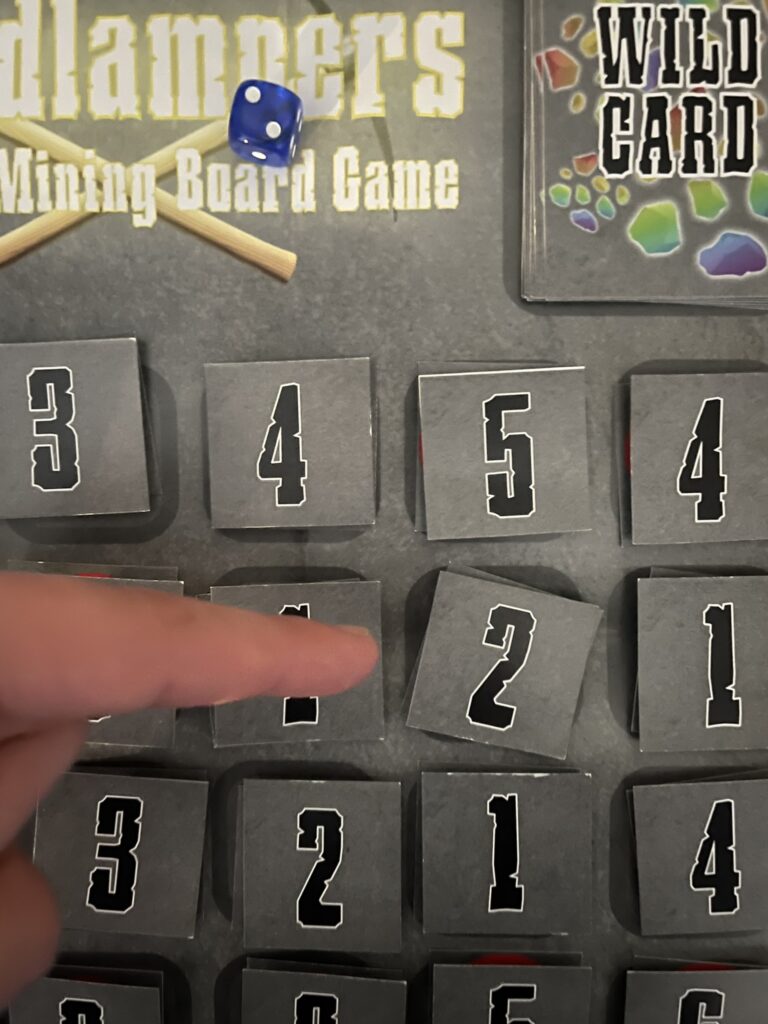

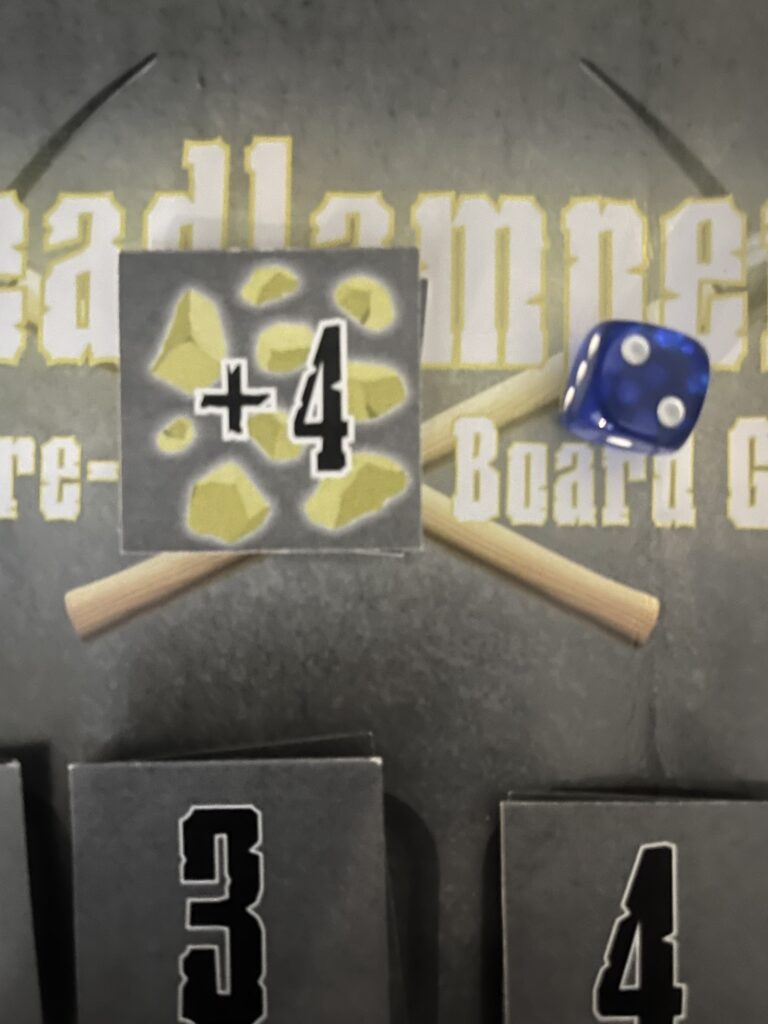

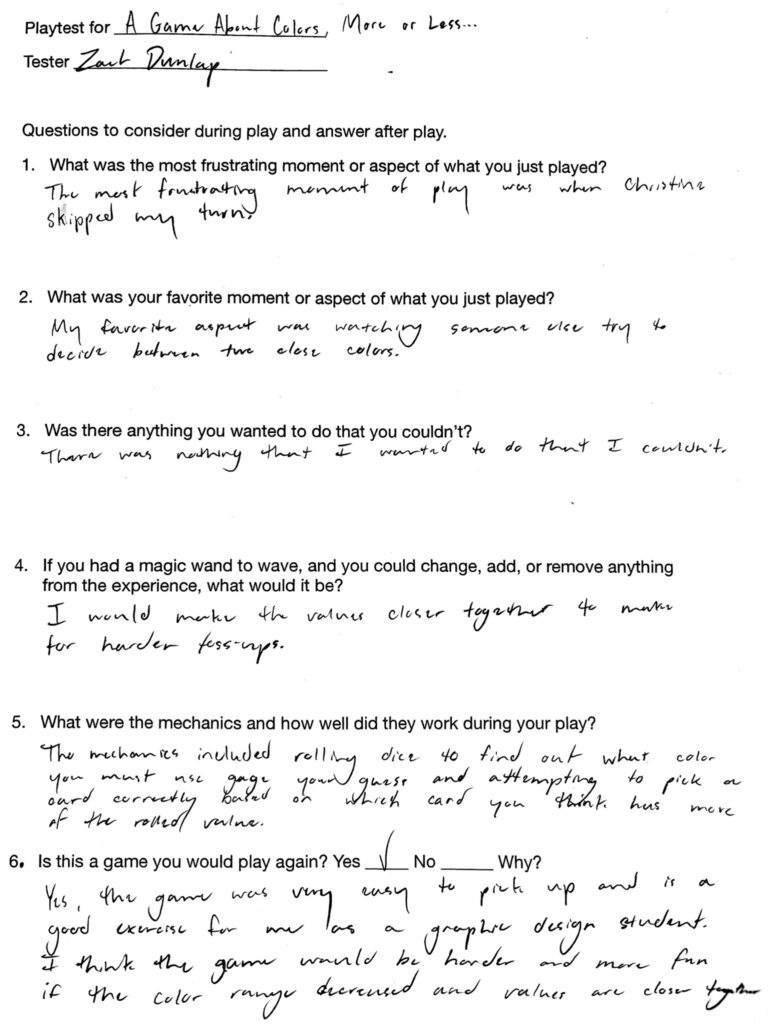

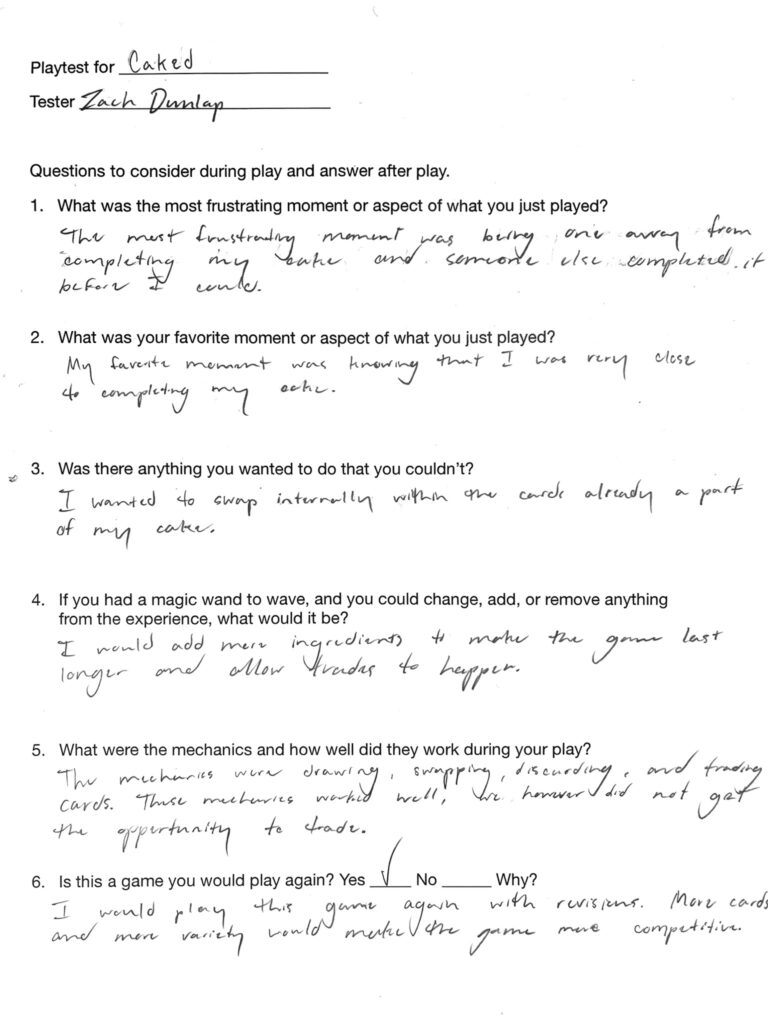

- The best game I made this semester, personally, was Headlampers. Headlampers is a board game in which the players take turns mining for ores by rolling dice and sabotaging their opponents with wild cards. The goals of the game are to end the game with the most points by collecting ores that will help you reach that goal, and attempting to lower the score of other players by drawing wild cards to sabotage opponents. In the event of a tie, a “pickaxe duel” must take place. Whoever rolls the higher number with the two dice is the true winner. The game is different each time, since tiles are detachable and randomized before each new round. Ore values are 1-5, 1 being the worst and 5 being the best. There are also bombs hidden within the board that have a value of -3. Wild cards occupy about 35%-40% of the board, and they prompt players to choose another to skip a turn, steal ores, or roll again, to name a few. Within playtesting, audiences liked the brevity and simplicity of the game. They liked how they didn’t need to use a ton of brain power, especially early in the morning.

Playtest Questions: Dessert Dash and Chef Check

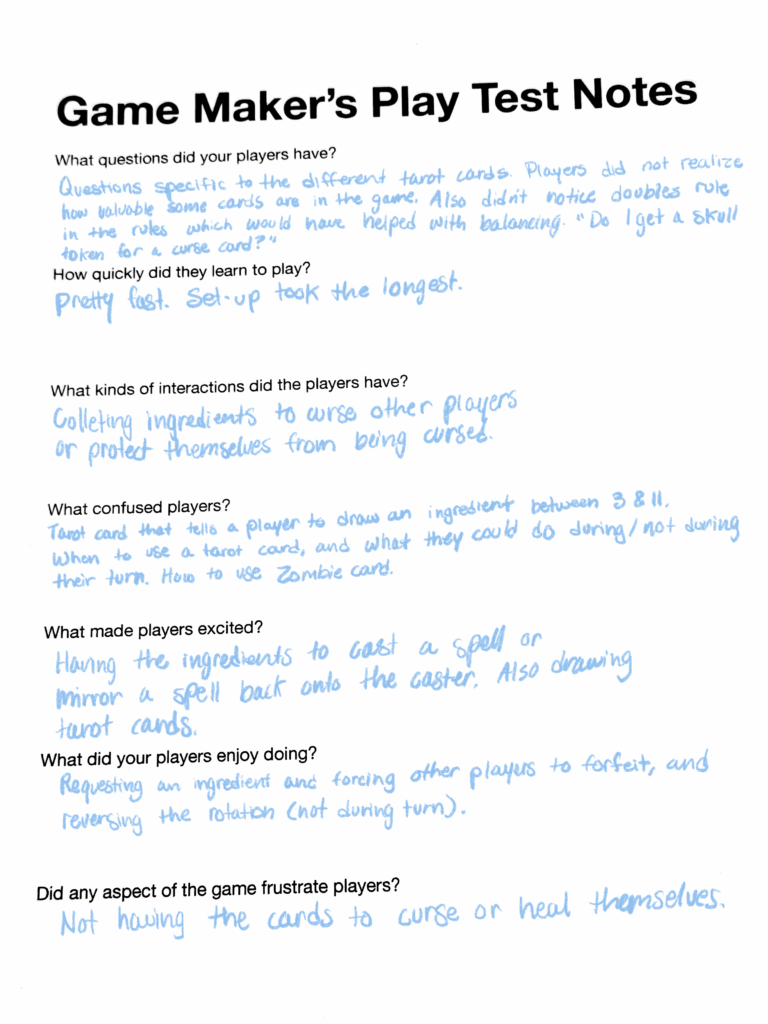

Game Maker’s Notes – Witch’s Brew

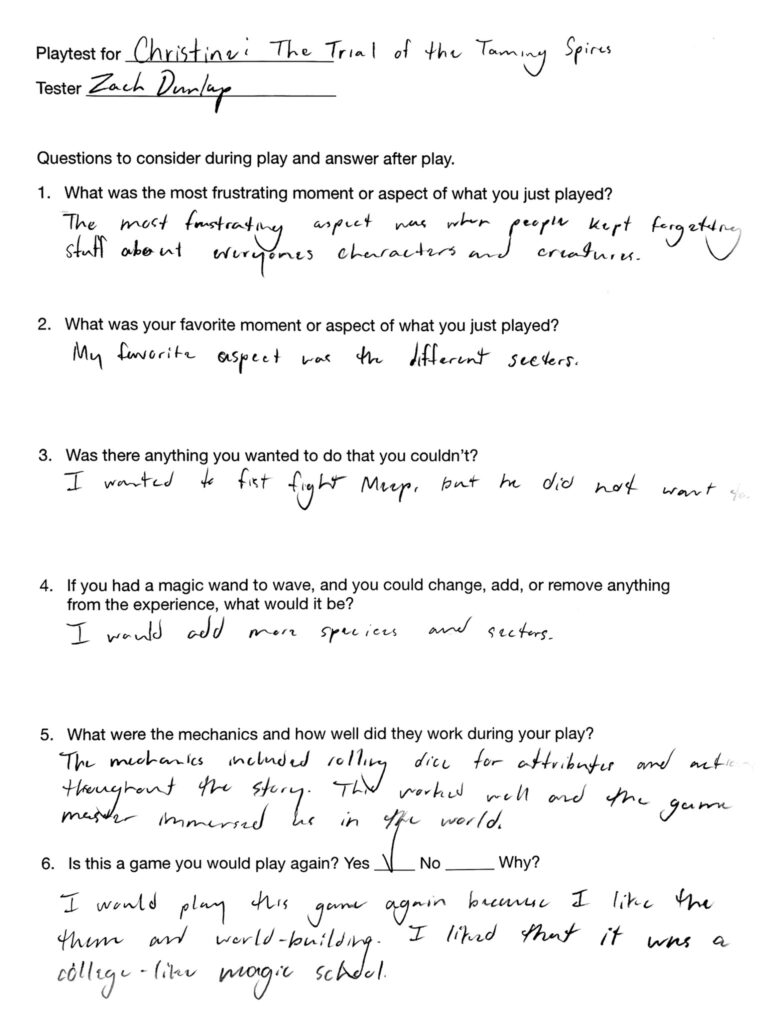

Playtest – The Trial of Taming Spires

2 Player Game Concept

Group: Maria Wack, Zach Dunlap

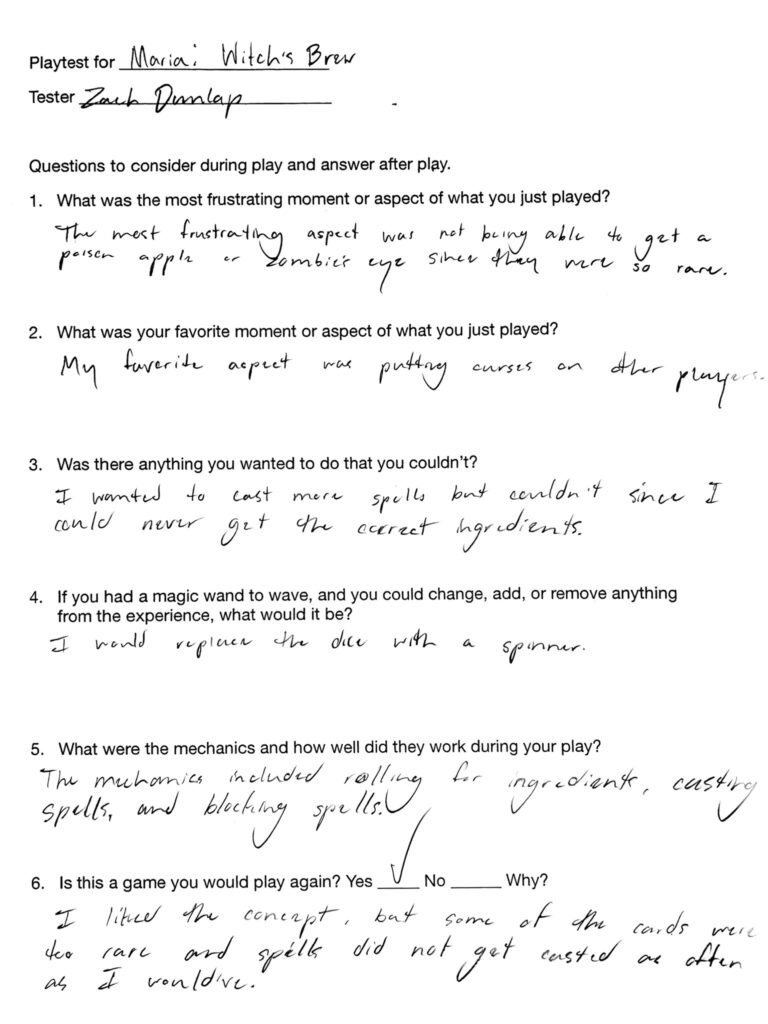

Playtest Questions: The Trial of the Taming Spires, Witch’s Brew

Headlampers (Version 2)

Headlampers (Version 1)

Week 8 Questions

Question Set 1

- Game developers usually don’t design the game; they enhance a designer’s game.

- Developers will try to push the boundaries of the game’s mechanics to see if they break.

- The number of components that need to be balanced, incorporating “costing”, and being okay with imperfect balance are challenges of balancing games.

- You can avoid stealing players’ fun by making sure they believe that there is a reasonable chance they can win until the very end.

- Use no intermediary terminology, use real words, make no more work than necessary, add flavor (but not too much flavor), make your text no smarter than your reader, discard rules that can’t be written, take a breath, go easy on the eyes, get your final version playtested, and fix it in the FAQ are 10 maxims you should follow when writing rules

Question Set 2

- Play-testing changed my games by making it easier to tweak rules based on the experience of the testers.

- I am open to anyone testing my next game or another version of one of my existing ones, but I would like Harmony to test my newest version of Headlampers.

- The audience for my game (Headlampers) is ages 6 and up.

- I think my roommates here at RMU and my friends from work should test my game outside of class.